Gutta-percha in endodontics – A comprehensive review of material science

Vijetha Vishwanath and H Murali Rao

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Abstract:

The complete and three-dimensional fluid tight seal of the root canal system is the final component of the endodontic triad. The long-standing and closest material which has fulfilled this criterion is gutta-percha (GP). Several materials have been tried and tested as an endodontic filling material, of which GP has been most extensively used for years and has established itself as a gold standard. In addition, it has proved itself successful with different techniques of obturation while maintaining its basic requisites. This article deals briefly with the history and evolution of GP, source, chemical composition, manufacturing, disinfection, cross-reactivity, and advancements in the material.

Keywords: Endodontics, gutta-percha, material science

INTRODUCTION

There is always on-going research for newer endodontic obturating materials to obtain better materials than the existing ones to fulfil the biological requisites along with predictable long-term treatment outcome. Several materials have been tried and tested for filling the root canal. The results were variable, from satisfactory to disastrous, at times. Of all the tested materials, gutta-percha (GP) has stood the test of time for years with consistent clinical performance under various clinical situations across the world. As of now, no other materials can be considered as a possible replacement for GP in its various forms. Hence, GP can be considered as a gold standard material for obturation.

HISTORY

History shows that GP has been used for a variety of purposes since the 17th century. Around 1656 an English natural historian John Tradescant introduced GP to Europe and called it “mazer wood.” In 1843, Dr. William Montgomerie further introduced GP to the West. His work was referred to the Medical Board of Calcutta and was awarded a gold medal by The Royal Society of Arts in London. The first patent for GP was obtained in 1864 by Alexander, Cabriot, and Duclos, which opened a Broadway for its industrial use. In 1845, Hancock and Bewley formed the GP Company in United Kingdom. People became infatuated with this new material and it became the first successful insulation for an underwater cable. Its use multiplied rapidly for manufacture of corks, pipes cements, thread, surgical instruments, garments, musical instruments, suspenders, window shades, carpets, gloves, mattresses, pillows, tents, umbrellas, golf balls (gutties), sheathing for ships, and boats were made wholly of GP.[1]

EVOLUTION OF GUTTA-PERCHA IN DENTISTRY

- 1846 – Alexander Cabriol surgical uses

- 1847 – Edwin Truman-GP-Temporary filling material

- 1847 – Hill-Hill’s stopping restorative material-Mixture of bleached GP, carbonate of lime and silica [2]

- 1849 – Chevalier, Poiseuille and Robert-GP tissue (laminated sheets)-Academy of Medicine, Paris

- 1864 – First patent by Alexander, Cabriot, and Duclos

- 1867 – Bowman-root filling material-St Louis Dental Society

- 1883 – Perry-Softened GP with gold wire

- 1887 – S. S. White Co.-Manufacture of GP

- 1893 – William Herbt Rollins-Modified GP with Vermillion

- 1911 – Webster-Heated GP-Sectional method of obturation

- 1914 – Callahan-Softening and dissolution of GP

- 1959 – Ingle and Levine-Standardized root canal instruments and materials

- Standardized GP – 2nd International Conference of Endodontics at Philadelphia

- 1967 – Schilder-Warm vertical compaction

- 1976 – International standards organization group for approval of specification of endodontic instruments and materials

- 1977 – Yee et al.-Injectable Thermoplasticized GP

- 1978 – Ben Johnson– Carrier based GP-Thermafil

- 1979 – McSpadden-Special compactor-Softening of GP by frictional heat

- 1984 – Michanowicz-Low temperature Injectable GP-Ultrafils

- 2006 – ANSI/ADA specification-GP cones-No.78.[3]

Some of commercially available GP points brand from earlier period (1970s) were manufactured by companies such as Dent-O-Lux, Indian Head, Mynol, Premier, and Tempryte. More recently, brands such as Tanari (Tanariman, Brazil), Meta (GN Injecta, Brazil), Dentsply (York, USA), Roeko (Coltene, Switzerland), Diadent (Korea), and Sybronendo (Orange, California) are popular since the evolution of NiTi rotary endodontic systems.

Apart from GP the alternate materials which have been tried are plastics (Resilon), solids or metal cores (Silver points, Coated cones, Gold, Stainless Steel, Titanium and Irridio-Platinum), and cements and pastes (Calcium Phosphate, Gutta Flow, Hydron, MTA). However, many of these materials do not meet the complete requirements for obturation of root canal systems. Only calcium silicate-based materials like MTA and related bioactive cements have shown promising results.

SOURCE

GP is a dry coagulated sap of a peculiar species of tropical plants. It was first obtained from Sapotaceae family of trees, which are abundant in the Malay Peninsula (South East Asia). In Malay-getah perca means “percha sap” (plant’s name). The trees are mainly found in Malay Archipelago, Singapore, Indonesia, Sumatra, Philippines, Brazil, South America, and other tropical countries. These trees are medium to tall (approximately 30 m) in height, and up to 1 m in trunk diameter. It is usually imported from Central South America for its use in dentistry, which is one of the reasons for its high cost.[4]

There are many species of Palaquium genus that yield GP of which four are found in India:

- P. obovatum-Assam

- P. polyanthum-Assam

- P. ellipticum-Western ghats

- P. gutta-Lalbagh Botanical garden, Bengaluru, Karnataka.

COMPOSITION

GP is a trans-isomer of polyisoprene. Its chemical structure is 1, 4, trans–polyisoprene. The molecular structure of GP is close to that of natural rubber from Hevea brasiliensis, which is a cis-isomer of polyisoprene. Both are high-molecular-weight polymers and structured from the same basic building unit or isoprenemer [Table 1].[1]

Table 1

Chemistry

| Natural rubber | Gutta percha |

| “Cis” polyisoprene | “Trans” polyisoprene |

| CH2 groups on the same side of the double bond to form the polymer of natural rubber | CH2 (Methylene group), groups on opposite sides of the double bond to form the polymer known as gutta-percha |

| More kinked, which complicates alignment, allows for mobility of one chain with respect to another, and gives natural rubber its elastomeric character | More linear and crystallizes more readily. Consequently, harder, more brittle, and less elastic than natural rubber |

MANUFACTURE

A series of “V” shaped or concentric cuts are made on the bark for the collection of milky juice in Areca palm conic receptacles. The juice is put into a pot and boiled with a little water to prevent its hardening on exposure to air. It is then boiled and kneaded under running water to remove particles of wood and bark; rolled into sheets to expel the air enabling it to dry quickly. It is placed in a revolving masticator and heated until it is fit for use. The chemical method of coagulation is by the addition of alcohol and creosote mixture (20:1), ammonia, limewater, or caustic soda.[2]

Obach’s technique

- The obtained pulp is heated to 75°C in the presence of water to release the GP threads (Flocculated GP known as “yellow gutta”) and then cooled to 45°C

- At below 0°C temperature, this yellow gutta is mixed with cold industrial gasoline to dissolve the resins and denature any residual proteins

- This mixture is dissolved in warm water at 75°C, and dirt particulates are allowed to precipitate

- The residual greenish-yellow solution is bleached with activated clay, filtered to remove any particulate, and then steam distilled to remove the gasoline

- The final commercially available formulation is “Final ultra-pure” (white) GP modified with appropriate fillers to overcome the odor of gasoline

- It is finally combined with fillers, radiopaque material, and plasticizers to obtain GP cones for endodontic procedures with the composition of 20% GP, 56% zinc oxide filler, 11% radiopacifier (barium sulfate), and 3% plasticizers (waxes or resins).[2]

In crude form, its composition is made of Gutta (75%–82%), Alban (14%–16%), Fluavil (4%–6%), and also tannin, salts, and saccharine. The elasticity of GP and its plasticity at elevated temperature is determined by Gutta. Alban does not seem to have any harmful effect on the technical properties of GP. Fluavil is a lemon-yellow, amorphous body, having the composition (C10H16O). When it occurs in gutta in larger quantities it renders this material brittle.

It is relatively easy to make GP sticks as not much of precision is required. However, to make endodontic cones, the precision of standardization has to be maintained. It requires a special technology where all ingredients are blended and passed through the specification molds running under high vacuum suction or by injection molding and hand rolling.[2,4]

CHEMICAL PHASES OF GUTTA-PERCHA

C.W Bunn in the year 1942, reported that the GP polymer could exist in two distinctly different crystalline forms, which he termed “alpha” and “beta” modifications. These forms were “trans” isomer, differing only in single bond configuration and molecular repeat distance, and hence could be converted into each other.

The “alpha” form occurs in the tree, which is the natural form. Most of the commercially available products are in the “beta” form. When the alpha form is heated >65°C, it becomes amorphous and melts. If this amorphous material is cooled rapidly, β form recrystallizes whereas if it is cooled extremely slowly (0.5°C/h), α form recrystallizes. The beta form becomes amorphous when heated at 56°C, which is a considerable 9° less than the melting point of the alpha form and the factor determining the melting point of “alpha” and “beta” GP is the rate of cooling which, in turn, controls the extent and character of crystallinity in the material formed [Table 2].[5]

Table 2

Characteristics

| Phases | Properties |

| Alpha (α) form | Brittle at room temperature Gluey, adhesive and highly flowable when heated (lower viscosity) Example: Thermoplasticised gutta-percha used for warm condensation obturation technique |

| Beta (β) form | Stable and flexible at room temperature Less adhesive and flowable when heated (high viscosity) Example: Commercially available gutta-percha used for cold condensation obturation techniques |

| Gamma (γ) form | Similar to α- form, unstable |

PHYSICAL AND THERMO-MECHANICAL PROPERTIES

GP is a thermoplastic and viscoelastic material which is temperature sensitive. At ranges of ambient room temperature, it exists in a stiff and solid state. It becomes brittle on prolonged exposure to light and air due to oxidation. It becomes soft at 60°C and it melts around 95°C–100°C with partial degradation. Decrease in temperature increase the strength and resilience and vice versa, especially when temperature exceeds 30°C.[6] The physical properties of tensile strength, stiffness, brittleness, and radiopacity depend on the organic (GP polymer and wax/resins) and inorganic components (zinc oxide and metal sulfates). Zinc oxide increases brittleness, decreases percentage elongation and ultimate tensile strength.[7] An account of the tensile strength of GP gives a reliable measure of its properties than compressive tests. Materials with the predominant property of ductility do not exhibit repeatable values for compression on account of resulting complicated stress patterns.

The property of viscoelasticity is critical during condensation of GP in obturation procedures which permits plastic deformation of the material under continuous load causing the material to flow.[6] The transformation temperatures of dental GP are 48.6°C–55.7°C for the β-to the α-phase transition, and 59.9°C–62.3°C for the α-to the amorphous phase transition, depending on the specific compound; heating dental GP to 130°C causes physical changes or degradation.[8]

An account of average values of few physical properties of some clinically usable GP points from various manufacturers is tabulated below. However, continuous modifications have been attempted over the years by the addition of various materials to improve the properties to result in better clinical performance [Table 3].[6]

Table 3

Physical properties of Gutta percha

| Physical properties | Average values |

| Yield strength | 1000-1300 psi |

| Resilience | 40-80 in/lb |

| Tensile strength | 1700-3000 psi |

| Elastic modulus | 15,500-28,000 psi |

| Flexibility | 0.07-0.12 in/lb |

| Elongation (%) | 170-500 |

PHYSICAL FORMS OF GUTTA-PERCHA

- Solid core GP points

Available as standardized and non-standardized points (beta phase).

-

- Standardized points: Correspond to instrument taper and apical gauge

- Nonstandardized points: Variable taper, the tip of point to be adjusted after apical gauging to obtain an optimum fit and apical seal.

Used with cold lateral condensation with warm vertical compaction.

- Thermomechanical compactable GP

- Thermo plasticized GP:

Available in injectable form (alpha phase). Special heaters are provided in the systems to attain flowable temperature of GP. The apical seal is accomplished with the plugging of master cone and then the injectable GP is backfilled.

-

- Solid core system

- Injectable form.[2]

- Cold flowable GP.

It is eugenol-free, self-polymerizing filling system in which the gutta percha in powder form is combined with a resin sealer in one capsule. It exhibits viscoelastic property of thixotropism and therefore has a better flow under shear stress which, in turn, provides good sealing ability.

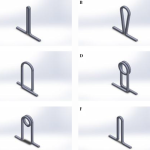

MODIFICATIONS OF GUTTA PERCHA

Attempts have been made to obtain optimum seal and therapeutic effects by addition of various materials [Figure 1].

Types of modified gutta percha

Surface modified gutta percha

One of the drawbacks of GP is lack of true adhesion. Hence, improvization for enhanced adaptability of GP has been attempted by surface modification with the following materials.

- Resin coated – A resin is created by combining diisocyanate with hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene, as the latter is bondable to hydrophobic polyisoprene (PI). This is followed by the grafting of a hydrophilic methacrylate functional group to the other isocyanato group of the diisocyanate, producing a GP resin coating that is bondable to a methacrylate-based resin sealer [9]

- Glass ionomer coated-Results in a true single cone monoblock obturation. Glass ionomer creates an ionic bond with the dentin, is nonresorbable and not affected by the presence of residual sodium hypochlorite

- Bioceramic coated-Bioceramic materials are incorporated and coated onto GP points which are available in specific sizes. They enhance the quality of obturation along with specific hydrophilic bioceramic sealers. These materials are in the form of nano particles (calcium phosphate silicates) to increase their activity and to bring about better sealing by taking advantage of the natural moisture of dentin. These kinds of obturation bring about slight expansion rather than the usual shrinkage, which actually is beneficial to seal the canals [10]

- Nonthermal plasma-Argon and oxygen plasma sprayed to GP improve the wettability of GP by the sealer, favoring adhesion. Argon plasma led to chemical modification and surface etching while oxygen plasma increased surface roughness.[11]

Medicated gutta-percha

- Iodoform: IGP contains 10% iodoform (CHI3), a crystalline substance, which is soluble in choloroform and ether but low solubility in water. They interact with cell walls of microorganisms causing pore formation or generate solid-liquid interfaces at the lipid membrane level, which lead to loss of cytosol material and enzyme denaturation. It is said to inhibit the growth of Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus sanguis, Actinomyces odontolyticus, and Fusobacterium nucleatum, but not Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa[12]

- Calcium hydroxide: Calcium hydroxide Gutta percha (CGG) points combine the efficiency of calcium hydroxide and bio-inertness of GP to be used as temporary intracanal medicaments. The action is directly correlated to the pH which is influenced by the concentration and rate of release of hydroxyl ions. When used as an intra-canal medicament in endodontic therapy, moisture in the canal activates the calcium hydroxide and the pH in the canal rises to the level of 12+ within minutes. The resultant antimicrobial effects may be evident within 1–4 weeks [13]

- Chlorhexidine: Chlorhexidine (CHX) is a broad-spectrum anti-infective agent which is a synthetic cationic bis-guanide. It acts by the interaction of the positively charged CHX molecule and negatively charged phosphate groups on microbial cell walls causing a change in osmotic equilibrium. CHX is both bacteriostatic (0.2%) and bactericidal (2%) and can penetrate the microbial cell wall by altering its permeability. Chlorhexidine impregnated GP points (Activ points) are known to be effective against E. faecalis and Candida albicans [14]

- Tetracycline: Tetracycline Gutta percha (TGP) contains 20% GP, 57% zinc oxide, 10% tetracycline, 10% barium sulfate, and 3% beeswax. They remain inert pending contact with tissue fluids; gets activated and become available to inhibit any bacteria that remain in the root canal or those that enter the canal through leakage. The greatest antimicrobial effect was seen on S. aureus and less on E. faecalis and P. aeruginosa[15]

- Cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC): CPC, a quaternary ammonium compound and a cationic surfactant, has been used in antiseptic products and drugs. Although the antimicrobial mechanisms of CPC are not well understood, it appears to damage microbial membranes, thereby eventually killing microbes. Addition of CPC improved the antimicrobial property of GP in proportion to the amount added. However, this GP is not commercially available yet.[16]

Nanoparticles enriched gutta-percha

The era of nanotechnology has turned into the best innovation in the fields of health sciences and innovation. Nano is derived from the Greek word “υαυος” which means dwarf, and it is the science of producing functional materials and structures in the range of 0.1 nm to 100 nm. Nano particulates show higher antibacterial action on account of their polycationic or polyanionic nature, which expands their applications in various fields.

Nanodiamond-gutta-percha composite biomaterials

Nanodiamond-GP composite embedded with nanodiamond amoxicillin conjugates was developed which could reduce the likelihood of root canal reinfection and enhance the treatment outcomes. NDs are carbon nanoparticles that are roughly 4μ – 6nm in diameter. It is a biocompatible platform for drug delivery, and they have demonstrated antimicrobial activity. Due to the ND surface chemistry, a broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as amoxicillin, can be adsorbed to the surface facilitating the eradication of residual bacteria within the root canal system after completion of obturation. The homogeneous scattering of NDs all through the GP matrix increases the mechanical properties, which enhance the success rate of conventional endodontic therapies and reduce the need for additional treatments, including retreats and apical surgeries.[17]

Silver nanoparticles coated gutta-percha

Silver (Ag) ions or salts possess sustained ion release, long-term antibacterial activity, low toxicity, good biocompatibility with human cells and low bacterial resistance. Dianat and Ataie have introduced nanosilver gutta-percha in an attempt to upgrade the antibacterial effect of GP, where the standard GP is coated with nanosilver particles. It demonstrates a significant antibacterial effect against E. faecalis, Staphylococcus aurous, Candida albicans, and E. coli.[18]

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Disinfection of gutta-percha

Handling, aerosols, and physical sources during the storage process can contaminate GP. The conventional process in which moist or dry heat is used cannot sterilize GP because this may cause irreversible physical or chemical alteration to the structure. Rapid chairside chemical disinfection is needed as the amount of GP points needed cannot be predicted beforehand. Sodium hypochlorite, glutaraldehyde, alcohol, iodine compounds, and hydrogen peroxide have been tried as GP cones disinfectant. The time ranges from a few seconds to substantial periods for these substances to kill microorganisms. NaOCl at 5.25% concentration is an effective agent for a rapid high disinfection level of GP cones. 2% CHX kills all vegetative forms in a short period but did not eliminate Bacillus subtilis spores within the times tested.[19] 2% peracetic acid solution is effective against some microorganisms in biofilms on GP cones at 1 min of exposure.[20]

Herbal extracts such as lemon grass oil, basil oil, and obicure tea extract, are probable alternatives for chairside disinfection of GP cones and have shown good results.[21] Ethanolic extracts of Neem, Aloe vera, and Neem + Aloe Vera have been seen to be successful in decontaminating GP cones against E. coli and S. aureus (common contaminants of GP cones).[22]

Removal of gutta-percha

GP solvents are used during retreatment or solvent based obturation technique as attempt in complete mechanical removal may cause perforation, straightening of canals or change in the internal anatomy compromising the tooth and treatment outcome. Benzene and carbon tetrachloride have been discontinued as solvents due to their toxicity. Others include eucalyptol oil, chloroform, methylchloroform, and xylene. The eucalyptol oil does not effectively dissolve GP at room temperature and has to be heated to act relatively fast. Hence, it not widely used. Chloroform is preferred due to volatility, cost, availability, better odor, and compatibility with zinc oxide-eugenol-based root canal sealers. Trichloroethylene, cineole, orange oil, Coe Paste Remover, halothane, anise oil, anethole, bergamot oil, terpineol in cineole, chlorobutanol in cineole, methoxyflurane, and diethyl ether have been tried and tested.[23]

BIOLOGICAL PROPERTIES AND TISSUE INTERACTION

Cross-reactivity

GP and gutta-balata are derived from the same botanical family as the rubber tree, and related to latex. It is reported that occasionally in the short supply of GP, the manufacturers add some amount gutta-balata or synthetic trans-polyisoprene to the GP cones which is not disclosed. It is seen that raw gutta-balata releases proteins that cross-react with Hevea latex and the use of a gutta-balata-containing product could potentially place a high latex allergic patient at risk for an allergic reaction even when proper instrumentation and obturation techniques are used to confine the material within the root canal system.[24]

Reaction of dental pulp

GP has been used as a temporary restorative material owing to its ease of placement and removal. The teeth become sensitive after its insertion into the dentin. Some of the teeth were extracted in an experimental study, and the histologic picture showed pathologic reaction in the pulp tissue, which changed with increasing observation period. The most typical reactions were:

- Odontoblast nuclei in the pulpal ends of the cut dentinal tubules [Table 4]

Table 4

Merits and demerits of gutta percha

| Merits | Demerits |

| Compactible | Lacks rigidity |

| Inert | Lacks adhesive quality |

| Can be softened | Does not bond to sealers by itself |

| Dimensional stability | Easily displaced by pressure |

| Tissue tolerant | Lack of length control |

| Radiopaque | |

| Easily removed | |

| Antibacterial | |

| Readily sterilizable |

- A break in the continuity of the pulp dentinal membrane

- Neutrophilic leukocytes along the predentine border, in the odontoblast layer and in the adjacent layer of Weil

- Capillaries in the odontoblast layer were filled with blood, and in most cases extravasated erythrocytes were scattered along with neutrophilic leukocytes and lymphocytes.[25]

Reaction of connective tissue

GP has been the least irritating root canal filling material till date. Fibrous encapsulation, calcification, and foreign-body reactions are some of the common responses to GP extruded into the periapical tissues. Small amounts of plasticizers, age resisters, coloring agents, and other additives do not play a major role in influencing the irritational qualities of GP cones. An inflammatory reaction is found only when an irritating material made up a significant percentage of the cone, as in calcium hydroxide enriched GP points. Therefore, the use of other additives should be kept to optimum levels.[26]

Reaction of gingival fibroblast and epithelial tumor cells

Increased connective tissue invagination with better healing of periradicular lesions have been attributed to calcium hydroxide and chlorhexidine-containing GP. Some authors described the destruction of epithelial tumor cells if present in periradicular lesions. Direct exposure of cells to the above materials has shown changes in cell morphology. The release of prostaglandin has been described as a helpful marker of inflammatory processes in pulp tissue. Conventional GP points have nonsignificant effect on the prostaglandin release by gingival fibroblasts. On contrary, some studies have shown that GP points containing calcium hydroxide or chlorhexidine, led to an inhibition of gingival fibroblast growth. Exposure of epithelial tumor cell cultures to the various tested materials led to morphological cell irregularities and influenced the proliferation patterns.[27]

Scaffolds

GP materials are primarily used for obturation, their interaction with living tissues is still being studied. Polybutadiene, a polymer with similar chemistry to PI, the base material of GP induces differentiation of dental pulp stem cells (DPSC), when its properties were modified by ZnO nanoparticles and dexamethasone. However, the mechanical strength and roughness imparted by the nanoparticles contributed to promoting differentiation of DPSC placed in contact with the material surfaces. It is probable that in addition to obturation, GP nanocomposites can act as scaffolds for dental tissue regeneration.[28]

MERITS AND DEMERITS OF GUTTA-PERCHA

Table 4 Merits and Demerits of gutta percha.

OTHER USES OF GUTTA-PERCHA

Assessment of pulp status

Thermal stimulation is a standard means of assessing the vitality of teeth and hot GP has conventionally been the most popular. As controlled temperature is difficult to attain, it is imperative that heated GP should not be in contact with the tooth surface for more than 3–5 s, else may result in damage of an otherwise healthy pulp. Rickoff et al. showed that GP used as above-increased pulp temperature only <2°C for <5 s of application – a temperature change that is unlikely to cause pulp damage.[29]

Tracing sinus tract

GP points are used to trace through sinus tracts to locate the source of infection and the offending tooth. Studies have indicated that GP is beneficial as a diagnostic adjunct and can be precise within 3 mm from the lesion. A medium-sized cone (size 25–40) has been found satisfactory due to its stiffness and ease of placement.[30]

Manual dynamic irrigation

GP points are used for manual agitation of irrigants in the root canal to improve the cleansing ability of debriding and disinfecting solutions to remove the smear layer.

Temporization

The base plate and temporary stopping GP are used for this purpose after intra coronal tooth preparation and for double seal during endodontic interappointment periods. However, zinc oxide eugenol cements provide a better seal than GP. Hence GP for this purpose should be used discretely.[31]

Assessment of intracoronal tooth preparation

Assessment of intracoronal tooth preparation was used to check undercuts in tooth preparation requiring indirect intracoronal restorations.

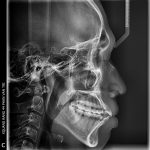

Markers for orthodontic and prosthetic implant placement

The use of guides for radiographic evaluation and surgical placement of dental implants can improve the final outcome of treatment for patients receiving implants. To aid in the determination of the ideal site for the implant, guides with markers are useful. A material to be used as a guide during a computed tomography scan, should contain no metal to eliminate the possibility of scatter. Since GP fulfills this criterion, possesses radiopacity and can be formed to a desired shape, it is the material of choice for this purpose.[32]

CONCLUSION

It can be concluded that the availability, ease of manipulation, chemical inertness, and cost effectiveness of GP along with newer techniques which are easy to adapt in clinical use have made this material indispensable in the field of endodontics.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Goodman A, Schilder H, Aldrich W. The thermomechanical properties of gutta-percha. II. The history and molecular chemistry of gutta-percha. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1974;37:954–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsare LD, Gade VJ, Patil S, Bhede RR, Gade J. Gutta percha – A gold standard for obturation in dentistry. J Int J Ther Appl. 2015;20:5. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash R, Gopikrishna V, Kandaswamy D. Gutta-percha: An untold story. Endodontology. 2005;17:32–6. [Google Scholar]

- Borthakur BJ. Search for indigenous gutta percha. Endodontology. 2002;14:24–7. [Google Scholar]

- Combe EC, Cohen BD, Cummings K. Alpha- and beta-forms of gutta-percha in products for root canal filling. Int Endod J. 2001;34:447–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman CE, Sandrik JL, Heuer MA, Rapp GW. Composition and physical properties of gutta-percha endodontic filling materials. J Endod. 1977;3:304–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniglia-Ferreira C, Silva JB, Jr, Paula RC, Feitosa JP, Cortez DG, Zaia AA, et al. Brazilian gutta-percha points. Part I: Chemical composition and X-ray diffraction analysis. Braz Oral Res. 2005;19:193–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniglia-Ferreira C, Gurgel-Filho ED, Silva JB, Jr, Paula RC, Feitosa JP, Gomes BP, et al. Brazilian gutta-percha points. Part II: Thermal properties. Braz Oral Res. 2007;21:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay FR, Loushine RJ, Monticelli F, Weller RN, Breschi L, Ferrari M, et al. Effectiveness of resin-coated gutta-percha cones and a dual-cured, hydrophilic methacrylate resin-based sealer in obturating root canals. J Endod. 2005;31:659–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manappallil JJ. Basic dental materials. JP Medical Ltd. 2015 Nov 30; [Google Scholar]

- Prado M, Menezes MS, Gomes BP, Barbosa CA, Athias L, Simão RA. Surface modification of gutta-percha cones by non-thermal plasma. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2016;68:343–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shur AL, Sedgley CM, Fenno JC. The antimicrobial efficacy of ‘MGP’ gutta-percha in vitro. Int Endod J. 2003;36:616–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde MN, Niaz F. Case reports on the clinical use of calcium hydroxide points as an intracanal medicament. Endodontology. 2006;18:23–7. [Google Scholar]

- Naik B, Shetty S, Yeli M. Antimicrobial activity of gutta-percha points containing root canal medications against E. faecalisand Candida albicans in simulated root canals–an in vitro study. Endodontology. 2013;25:8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bodrumlu E, Alaçam T, Semiz M. The antimicrobial and antifungal efficacy of tetracycline-integrated gutta-percha. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:112–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomino M, Nagano K, Hayashi T, Kuroki K, Kawai T. Antimicrobial efficacy of gutta-percha supplemented with cetylpyridinium chloride. J Oral Sci. 2016;58:277–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DK, Kim SV, Limansubroto AN, Yen A, Soundia A, Wang CY, et al. Nanodiamond-gutta percha composite biomaterials for root canal therapy. ACS Nano. 2015;9:11490–501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shantiaee Y, Maziar F, Dianat O, Mahjour F. Comparing microleakage in root canals obturated with nanosilver coated gutta-percha to standard gutta-percha by two different methods. Iran Endod J. 2011;6:140–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes BP, Vianna ME, Matsumoto CU, Rossi Vde P, Zaia AA, Ferraz CC, et al. Disinfection of gutta-percha cones with chlorhexidine and sodium hypochlorite. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:512–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvia AC, Teodoro GR, Balducci I, Koga-Ito CY, Oliveira SH. Effectiveness of 2% peracetic acid for the disinfection of gutta-percha cones. Braz Oral Res. 2011;25:23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makade CS, Shenoi PR, Morey E, Paralikar AV. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity and efficacy of herbal oils and extracts in disinfection of gutta percha cones before obturation. Restor Dent Endod. 2017;42:264–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natasha FA, Dutta KU, Moniruzzaman Mollah AK. Antimicrobial and decontamination efficacy of neem, Aloe vera and neem+ Aloe vera in guttapercha (gp) cones using Escherichia coliand Staphylococcus aureus as contaminants. Asian J Microbiol Biotech Environ Sci. 2015;17:917–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wourms DJ, Campbell AD, Hicks ML, Pelleu GB., Jr Alternative solvents to chloroform for gutta-percha removal. J Endod. 1990;16:224–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa GE, Johnson JD, Hamilton RG. Cross-reactivity studies of gutta-percha, gutta-balata, and natural rubber latex (Hevea brasiliensis) J Endod. 2001;27:584–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James VE, Schour I, Spence JM. Response of human pulp to gutta-percha and cavity preparation. J Am Dent Assoc. 1954;49:639–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson EM, Seltzer S. Reaction of rat connective tissue to some gutta-percha formulations. J Endod. 1975;1:395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willershausen B, Hagedorn B, Tekyatan H, Briseño Marroquín B. Effect of calcium hydroxide and chlorhexidine based gutta-percha points on gingival fibroblasts and epithelial tumor cells. Eur J Med Res. 2004;9:345–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Yu Y, Joubert C, Bruder G, Liu Y, Chang CC, et al. Differentiation of dental pulp stem cells on gutta-percha scaffolds. Polymers. 2016;8:193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickoff B, Trowbridge H, Baker J, Fuss Z, Bender IB. Effects of thermal vitality tests on human dental pulp. J Endod. 1988;14:482–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldassari-Cruz LA, Walton RE. OR 3 effectiveness of gutta percha tracing sinus tracts as a diagnostic aid in endodontics. J Endod. 1999;25:283. [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar JS, Suresh Kumar BN, Shyamala PV. Role of provisional restorations in endodontic therapy. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2013;5:S120–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesun IJ, Gardner FM. Fabrication of a guide for radiographic evaluation and surgical placement of implants. J Prosthet Dent. 1995;73:548–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Articles from Journal of Conservative Dentistry : JCD are provided here courtesy of Wolters Kluwer — Medknow Publications